Paul Harris as I knew Him

I never knew a fellow like Paul Harris. Of all the men I ever met, I couldn’t choose one better fitted to be the Founder of Rotary.

I never knew a fellow like Paul Harris. Of all the men I ever met, I couldn’t choose one better fitted to be the Founder of Rotary.

Why? Well, there’s no simple answer to that question because Paul had as many sides as a centipede has feet. Speakers will tell you he was a man of noble ideals, a profound thinker, and a leader gifted with imagination. I agree. But as I think back over our many years as friends, I can say truthfully I have known no one to get more fun out of just being human. If there’s a secret to Paul’s success, it’s that he just naturally liked people.

Physically, he wasn’t a big fellow, certainly not the halfback type at all, though he played razzle‑dazzle football in his prep-school days. When he hung out his shingle as a lawyer in Chicago, back in 1896, he was a handsome chap. Most Rotarians are familiar with his picture as a serious, baldheaded, middle‑aged man. But you should have seen him when he had a full head of dark hair and a mustache. In those days he could swing as dapper a cane and wear as smart a derby on Sunday walks along Lake Michigan as any young bachelor in Chicago.

Wherever he went, he would stop and talk to folks. It didn’t make any difference who. He always seemed restless to meet more people and to know how they lived. Though born in Racine, Wisconsin, in 1868, he was raised by his father’s parents in quiet New England at Wallingford, Vermont. Most boys are satisfied to complete their college career at one school. Not restless Paul. He spent a year at the University of Vermont, another at Princeton University, and finished up in law at the University of Iowa.

Then while most of his classmates were settling down, Paul did a characteristic thing. He earmarked the next five years of his life to see the world. Yellowstone Park called. Then San Francisco, where he worked on a newspaper and a fruit farm. He taught in a Los Angeles business college; “punched cows” near Platteville, Colorado; clerked in a hotel in Jacksonville, Florida, and became a salesman there for Vermont granite. Before his five years were up, he had worked his way to England on a cattle boat and bicycled all over the Continent.

His five‑year “apprenticeship to living” being over, he settled in Chicago, a young lawyer very much in need of paying clients. It was business that brought Paul and me together, as I have already noted, and was the magnet that drew the early members into our Rotary Club. Yet with the profit appeal went fellowship, and under Paul’s leadership the emphasis became less and less “selfish” and more and more on fellowship with idealistic goals that naturally suggested themselves.

Silvester Schiele, the coal dealer, was Paul’s first convert to his idea for a new club. Official Rotary Global History says that they had dinner, then met with Gus Loehr a mining engineer, and his friend Hiram Shorey, a tailor, at Gus’ office on February 23, 1905. I was at the next session, becoming the fifth Rotarian.

Gus and Hiram dropped out within a short time. But what these two lacked in enthusiasm was made up by others, for example Will R. (“Doc”) Neff, a dentist, and later “Pete” Powers, who had been on the stage and livened our meetings with fun. When interest sagged so low in 1906 that we considered disbanding, a handful of us kept the Club alive. Doc slaved for Rotary more than 15 years, day and night, as Financial Secretary. Never got a nickel for it. Pete was a good running mate. If either promised to do something, it was as good as done.

LET me also pin a rose on two other old‑timers, Charlie Newton and A. M. (“Red”) Ramsay. “Red†is gone, but Charlie lives in Los Angeles, where he still carries on in insurance and keeps up the finest private collection of old Rotary documents in existence. We used to call him “watchdog of the Constitution” because he was, and is, a great arguer.

As for my own part in early days of No. 1, I concentrated on the practical problem of getting new members. Paul Harris was a good writer and put out bales of pamphlets and letters, leaving recruiting largely to me. I liked this because I always was a mixer and felt that out of our 1,000 or so print‑shop customers, quite a few would be glad to join. They were. Once I had a list of 150 members I recruited. But success went to our heads, I’m afraid.

Have you ever heard of Rotary “Yellow Dogs”? I sort of hope not‑yet because they taught us a lesson. I’ll tell the story. Up to 1909 our membership ran about 190. Then we, and I guess I was one of the pushers, thought we should have a lot more. So I printed a circular listing “open classifications” saying we expected every Rotarian to do his duty by bringing in at least one new member. Those who didn’t had to wear outlandish paper hats, sit at an old board table, and with tin spoons eat soup and hash from tin dishes. They were Yellow Dogs. The rest of us feasted like kings at the other end of the room.

I don’t recommend the Yellow Dog idea for any Club! It brought in new members, of course, but before long it was plain as Jimmy Durante’s nose that we had made a mistake. We had gone after quantity when we should have concentrated on quality.

Yet, if I may speak up for myself, I’ll say my record wasn’t too bad, because I brought Chesley R. Perry into Rotary. That was in 1908. Ches was a veteran of the Spanish‑ American War, had had newspaper experience, was interested in investments in Mexico and worked in the Chicago Public Library. His tremendous vitality and organizing ability were poured into Rotary in 1910 when Paul Harris persuaded him to be Secretary of what was to become Rotary International. Ches slaved on that job till 1942, 32 fruitful years. In “My Road to Rotary” Paul says, “If I can in truth be called the architect, Ches can with equal truth be called the builder of Rotary International.”

Yet, if I may speak up for myself, I’ll say my record wasn’t too bad, because I brought Chesley R. Perry into Rotary. That was in 1908. Ches was a veteran of the Spanish‑ American War, had had newspaper experience, was interested in investments in Mexico and worked in the Chicago Public Library. His tremendous vitality and organizing ability were poured into Rotary in 1910 when Paul Harris persuaded him to be Secretary of what was to become Rotary International. Ches slaved on that job till 1942, 32 fruitful years. In “My Road to Rotary” Paul says, “If I can in truth be called the architect, Ches can with equal truth be called the builder of Rotary International.”

Back in 1909, Ches had a part in an event which, though unfortunate at the time, taught our young Club a lesson. Someone got the idea that we should have hot election rivalry, so the Club was a divided arbitrarily into two groups, “Reds” and “Blues.” Ches headed up one ticket and “Red” Ramsey the other. “Red” won, but though Ches was a good sport so about it we realized that hard feelings had developed among certain members and that hot fights in Club elections didn’t promote the Club’s health.

But back again, to the early days. Paul would often give me a ring, and we’d meet in a winestube on Dearborn Street and talk by the hour about ways to get new members, about programs, and so on. Often he came to suburban Hinsdale, spending the week‑end with Josephine and me. Sometimes he became discouraged about Rotary, but usually wasn’t.

PAUL seemed the logical on to be first President, but he insisted that Silvester Schiele have the honor. Silvester was followed by A. L. White, but by 1907 Paul couldn’t hold out longer against pressure and accepted the position, and again in 1908. But already he had a bee in his bonnet that Rotary could become a national, perhaps international organization. When he resigned the Presidency in October, 1908 he poured his enthusiasm into extension.

Our second Club was started in 1908 in San Francisco while I was President of No. 1. Oakland followed soon, then Seattle, Los Angeles, and New York. An incident connected with starting in New York throws such light on Paul Harris’ zeal that perhaps I should mention it.

Paul had persuaded Fred Tweed to get things going there and thought Fred should be paid his out‑of‑pocket expenses. Knowing the close race between our income and our expenses‑dues were but $12 a year! I insisted that the Club decide. In fact, I was a bit wary about taking on more extension than we could chew, as this, the fifth plank in my Presidential platform, shows:

“While I believe it would be ideal to have a Rotary Club in every large city and have a national organization with headquarters in Chicago, still I believe that we should go about this with caution. This matter should be discussed in all its phases at a meeting of the Directors. I do not want to take the responsibility of this work and a Committee will have to take it and submit a plan for the Club’s consideration.”

[the committee included Ches Perry, and a comment in “My Road to Rotary” by Harris expands on this slightly tense time]

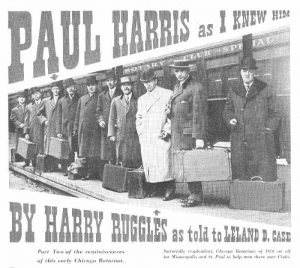

Fortunately, Paul Harris’ enthusiasm carried the day and Fred Tweed was reimbursed. If I was lukewarm at first about new Clubs, I soon became hot doing what I could by song leading to help make the first Convention a success. It was held in Chicago in 1910 and resulted in the organization of the National Association of Rotary Clubs in America. That’s the year ten of us Chicago Rotarians paid our own way to Minnesota to launch Clubs in Minneapolis and St. Paul. Then in 1912‑13 as one of President Glenn C. Mead’s Directors, with the help of Chesley Perry, we got Clubs organized in Peoria, Illinois, and Indianapolis, Indiana. Today nobody in the wide, wide world is prouder of the way Rotary has grown than Harry Ruggles.

Maybe up to now I’ve given you the idea we early Rotarians were too serious. In a way we were, but in most ways we weren’t. And when there was fun to be had, Paul was usually the ring leader. He would keep a poker face, until the right time, then laugh until his whole body would shake.

He was a great fellow to promote a week‑end picnic. Often it was across Lake Michigan at Paw Paw Lake or Dowagiac, where his bachelor friend Tom Clybourn had an ideal, well‑stocked place for letdowns. We would fish or swim, paddle a canoe or play baseball .. well, do about everything. Each would kick in $10 to “Doc” Neff for a “kitty” ‑but expenses were light, so “Doc” usually would declare a Monday “dividend.”

Once Paul led the bunch on a weekend hike in the sand‑dune country along the south end of Lake Michigan. Just where I don’t remember, but I know that after a long, long hike some of us wanted to turn back.

“All right,” said sober‑sided Paul, “we’ll walk back to the station and catch the interurban to Chicago.”

He led the way. We walked and we walked and the sun was beating down. We were sweaty and plenty tired when a farmhouse dame into view. When one of our fellows – we called him “Dipper” Smith ever afterward‑saw the well, he galloped up like a horse and drank two quart dipperfuls of water.

“Got any beer?” he asked the farmer’s wife.

“Come on in and we’ll see,” she said. As she opened the door, there was a table spread for us, groaning with every sort of food a farmer’s wife could lay out. Of course, Paul had arranged it all. And did he chuckle!

That night We slept in the barn. Next morning Paul suggested that he and I go to church. It was a Swedish church, but that made no difference to Paul. He enjoyed every minute of it, especially when he and I in our loudest voices joined in singing Swedish hymns of which we understood not a word.

In our earliest days we didn’t have regular programs, remember. Partly for fun, partly to startle new members into realizing they really were joining something, we initiated them. Often we’d tell the newcomer to sing, say, Auld Lang Syne or, maybe, give a speech on the future of the horseless carriage. He’d hardly have his mouth open before a hook from the wings would yank him offstage to the accompaniment of catcalls. Pete Powers generally arranged such events and sometimes would have the neophyte wear his coat inside out, then crawl beneath outspread legs of members, with, of course, a few well‑placed pats.

One night we had a comedy boxing match between Harry Crofts, weight 250, and Les Lawrence, who barely tipped the scales at 95 pounds. It finished with Harry playing a mouth organ as he carried Les on his shoulders around the room. Kid stuff, sure! It seemed good fun then, though.

And practical jokes! One of our best was on Rufus (“Rough House”) Chapin, banker and later the long‑time Treasurer of Rotary International. We were dining at the Virginia Hotel that night when a woman (an excellent actress we’d hired) with a squalling babe in her arms came up to “Rufe,” said he was the baby’s father, and begged money to buy milk. “Rufe” was a bachelor and plenty embarrassed, especially when the morning paper carried a story on the hoax!

Another prank was pulled on Barney Arntzen, the undertaker. One night he responded to a hurry‑up telephone call from the Southern Hotel, where Paul Harris and Silvester Schiele were living, I should add. Barney was very, very professional in manner until he started to shift the corpse. It moved! As he lifted the sheet, Pete Powers grinned up as the whole bunch of yelling Rotarians burst into the room, I might as well admit I was on the receiving end of as successful a stunt as the Club ever had. Somebody promoted a fight between a badger and a bull dog, to be held in a South Side roller‑skating rink. There was a lot of publicity about how the ferocious badger would claw the dog and I, being fond of dogs, thought maybe I could save the dog from death, so consented to be referee. Only my Josephine kept me from wearing a dress suit for the occasion. More than 300 people were there, and at the proper moment I tugged the strap to bring out the badger. Instead, I pulled out a large vessel that had no proper place in public. The build‑up had been so perfect I was completely flabbergasted, Of course I stood treats that time!

But we carried such things too far, and the prank that made us all realize it was one played on Paul Harris shortly after his second term as President started in 1908. One night at a dinner in the Bismarck Hotel our member Congressman George P. Foster, a surety-bond man, got the floor and in an eloquent spiel scored Paul for being “dictatorial” and said he was resigning then and there from the Rotary Club. Of course a few of us spoke up in Paul’s defense as planned, but others had been primed to follow up George Foster’s remarks.

As one after another sat down, Paul’s face got red. No one knew how deeply he was hurt, I guess, not until he arose and solemnly said no one else need resign because he was resigning. Paul then. walked out of the room in a huff. Of course we immediately sent a committee out to find him. The fellows informed Paul that at long last we had pulled a joke on him!

Maybe I shouldn’t even be mentioning that incident. But it seems to me worth recalling for two good reasons. One is that it shook us up, and from then on, we began to grow up as a Club. We had fun, yes, but fun that didn’t leave a hurt. The other is that it revealed in a new way the character of Paul. He held nothing against anyone. He pitched in as hard as before to make meetings interesting and enjoyable, to get new members, and to organize new Clubs. Nor did the experience dampen his love of fun with fellowship.

Till the day he died there was a lot of the boy in Paul. He could be as serious as any lawyer, then at the next moment he would do the most unexpected and amusing thing. Why, I remember once when Fred Tweed had an art party, all of us were to wear smocks and draw from models. Paul turned an aerial somersault from the straps in a streetcar. He had more new ideas in a minute than most of us had in a week.

On his trips around the world with Jean, his bonnie Scottish Lassie, he could be as dignified upon occasion as anyone could expect a representative of Rotary to be, but always he was ready to join in play. When Copenhagen Rotarians dressed him up like a Danish maiden, flaxen wig and all, he enjoyed it. In Australia, where people got their ideas about Chicago from gangster movies, Rotarians staged a fake holdup “just to make you feel at home” and he got a kick out of that.

On his trips around the world with Jean, his bonnie Scottish Lassie, he could be as dignified upon occasion as anyone could expect a representative of Rotary to be, but always he was ready to join in play. When Copenhagen Rotarians dressed him up like a Danish maiden, flaxen wig and all, he enjoyed it. In Australia, where people got their ideas about Chicago from gangster movies, Rotarians staged a fake holdup “just to make you feel at home” and he got a kick out of that.

No, there was nothing of the stuffed shirt about Paul Harris. Though he had sparked Rotary’s growth from a handful of men at first chiefly interested in swapping business with each other into a world‑wide idealistic movement, he insisted always that the heart of Rotary was fellowship and that fellowship was to be enjoyed.

Paul left us, you remember, one snowy day in January, 1947. Some well-intentioned people were all for making him a sort of a saint. But nothing would have been further from his sincerest desire. He had honors galore, degrees from universities, and medals from Governments, yet always he was the same simple person who above everything else treasured and enjoyed his friends.

He didn’t build grandiose castles in the air about Rotary changing the world, either. Just as he was personally humble, so he was restrained in his concept of what Rotary is and can do.

“If Rotary has encouraged us to take a more kindly outlook on life and men,” he once said, “if Rotary has taught us greater tolerance, and the desire to see the best in others; if Rotary has brought us helpful and pleasant contacts with others, who are also trying to capture and radiate the joy and beauty of life, then Rotary has brought us all that we can expect.”

From the March 1952 copy of The Rotarian, acquired and scanned by Wolfgang Ziegler 17 September 2003